Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Saturday, November 26, 2011

Lateral Epicondyle Injection

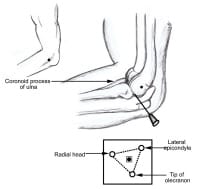

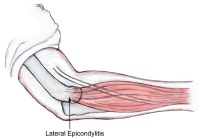

- I saw patient with tennis elbowLateral epicondylitis of the elbow involves pathologic alteration in the musculotendinous origins of the extensor carpi radialis brevis and longus tendons (see image below).[1, 2, 3, 4]

Lateral epicondyle.

Lateral epicondyle. - Though commonly known as tennis elbow, lateral epicondylitis may be caused by various sports and occupational activities.

- The diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis is based upon a history of pain over the lateral epicondyle and the following findings on physical examination:

- Local tenderness directly over the lateral epicondyle

- Pain aggravated by resisted wrist extension and radial deviation

- Decreased grip strength or pain aggravated by strong gripping

- Normal elbow range of motion

- Strain or tear of various portions of the extensor digitorum and extensor carpi radialis brevis muscles due to repetitive use results in chronic inflammation.[5]

- The histopathology of the affected musculature reveals edema and fibroblast proliferation in the subtendinous space, tendinopathy with hypervascularity (particularly involving the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon), and spur formation with a sharp longitudinal ridge on the lateral epicondyle.

- Corticosteroids and other drugs often are injected in and around soft-tissue periarticular lesions to treat regional pain syndromes.

- The principles and practice of inserting a needle into a joint cavity are very similar to the principles and practice of inserting a needle into a periarticular lesion.

Indications

- Failure of conservative treatment

- To shorten symptomatic period (long-term outcome is similar in patients who do or do not receive injection)[6, 7]

- To speed up recovery in high-performance athletes, although this is a controversial practice

Contraindication

- oint or soft-tissue aspirations and injections have few absolute contraindications.

- The procedure should probably be avoided if the overlying skin or subcutaneous tissue is infected or if bacteremia is suspected.

- The presence of a significant bleeding disorder or diathesis or severe thrombocytopenia may also preclude joint aspiration.

- Aspiration of a joint with a prosthesis in it carries a particularly high risk of infection and is often best left to a surgeon using full aseptic techniques.

- Lack of response to previous injections may be a relative contraindication.

- If infection is suspected as the underlying cause of the musculoskeletal problem, injection of corticosteroids must be avoided for fear of exacerbating the infection. Corticosteroids are contraindicated in patients with septic arthritis.

- Warfarin anticoagulation with international normalization ratio (INR) values in the therapeutic range is not a contraindication to joint or soft-tissue aspiration or injection.

Anesthesia

- Experienced clinicians often prefer to use topical ethyl chloride or no anesthetic at all.

- This is often appropriate for joint aspiration, as the capsule is difficult to anesthetize, and a single quick needle thrust may be much less painful than the administration of local anesthesia

Equipment

Aspiration or injection of soft tissues may be performed as an outpatient procedure and does not require specialized equipment.[8]- Needle, 25 or 27 gauge

- Readily available syringes for injection (3-5 mL)

- Methylprednisolone acetate 20-40 mg

- Lidocaine 1% (0.5-1 mL) without epinephrine

Positioning

- Place the patient in a comfortable, supine position. This aids relaxation and guards against possible fainting.[1]

- Have the patient flex the affected elbow to 90° with the hand tucked under the buttock.

- Mark the lateral epicondyle and radial head

- Follow sterile precautions throughout the procedure.

- Clean the skin carefully with antiseptic agents.

- Ethyl chloride may be applied to the skin for anesthesia.

- Inject the corticosteroid and local anesthetic into the common extensor tendon origin at the lateral humeral epicondyle.

- Infiltrate the corticosteroid deeply at the tenoperiosteal junction.

- A painful reaction to injection or firm resistance during injection suggests that the needle is too deep and is within the body of the tendon; withdraw the needle 1/8 inch if this occurs.

- The needle should move freely with skin traction if the tip is above the tendon; conversely, the needle sticks in place if the tip is within the body of the tendon.

- Inject the corticosteroid at the tissue plane between the subcutaneous fat and the tendon.

- At the end of injection, withdraw the needle swiftly and apply light pressure to the needle site.

Pearls

- Corticosteroid injections and infiltrations are basic treatment tools in rheumatology, orthopedics, physiatry, and general medicine.

- Corticosteroid injections and infiltrations carry minimal risk to the patient when properly indicated and performed.

- Technical difficulties vary; some of these procedures require specialized knowledge for optimal results.

- Precaution: Avoid injecting too superficially.

- Lack of improvement with lidocaine infiltration suggests an alternative diagnosis, such as compressive neuropathy of the deep branch of the radial nerve or cervical radiculopathy.

- Reinjection may be necessary in 4-6 weeks if symptoms have not been reduced by at least 50%.

- Surgical consultation can be considered if 2 injections combined with wrist immobilization fail to resolve the condition.

- For chronic cases, no more than 4 injections should be performed in the same arm.

Complications

Surprisingly few complications arise as results of these procedures.[1, 2]- The most significant issue is the risk of infection. Care must always be taken to use sterile techniques. Corticosteroids are contraindicated in patients with septic arthritis.

- The estimated risk of septic arthritis following a corticosteroid injection is on the order of 1 per 15,000 procedures.[9]

- Patients with severe immunodeficiency or implants may be at greater risk of complications.

- Other complications can arise from misplaced injections.

- The best-described complication is tendon rupture following corticosteroid injections for tendonitis. The risk of this complication can be minimized by avoiding injection into the tendon itself. No therapeutic agent should be injected against any unexpected resistance.

- Occasionally, nerve damage can also result from a misplaced injection (eg, median nerve atrophy following attempted injections for carpal tunnel syndrome).

- Transient increase in pain is seen in 20-40% of patients.

- Repeated corticosteroid infiltrations may result in chronic pain.

- Superficial corticosteroid infiltrations often cause a hypopigmented patch, which may be quite disfiguring in people with dark skin. The condition resolves in a few months to 2 years.

- Skin atrophy is a frequent complication of superficial infiltrations.

- Rarely, corticosteroid injections can cause transient pituitary inhibition that lasts up to several days. Serial infiltrations may cause adrenal suppression and result in acute adrenal crisis.

Thursday, November 24, 2011

The Limping Child: A Systematic Approach to Diagnosis

Deviations from a normal age-appropriate gait pattern can be caused by a wide variety of conditions. In most children, limping is caused by a mild, self-limiting event, such as a contusion, strain, or sprain. In some cases, however, a limp can be a sign of a serious or even life-threatening condition. Delays in diagnosis and treatment can result in significant morbidity and mortality. Examination of a limping child should begin with a thorough history, focusing on the presence of pain, any history of trauma, and any associated systemic symptoms. The presence of fever, night sweats, weight loss, and anorexia suggests the possibility of infection, inflammation, or malignancy. Physical examination should focus on identifying the type of limp and localizing the site of pathology by direct palpation and by examining the range of motion of individual joints. Localized tenderness may indicate contusions, fractures, osteomyelitis, or malignancy. A palpable mass raises the concern of malignancy. The child should be carefully examined because nonmusculoskeletal conditions can cause limping. Based on the most probable diagnoses suggested by the history and physical examination, the appropriate use of laboratory tests and imaging studies can help confirm the diagnosis

Figure 3.

Internal rotation of the hip is measured by placing the child in the prone position with knees flexed 90 degrees and rotating the feet outward. Loss of internal rotation is a sensitive indicator of intraarticular hip pathology and is common in children with Legg disease and slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

Figure 4.

Hip abduction is measured by placing the child in the supine position with hips and knees flexed and the toes placed together. To measure abduction, both knees are allowed to fall outward. Limited hip abduction, as in this child’s left hip, occurs in children with developmental dysplasia of the hip.

Reprinted with permission from Storer SK, Skaggs DL. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(8):1313.

Figure 5.

Positive Galeazzi sign. The child is placed in the supine position with the hips and knees flexed. In a positive test, the knee on the affected side is lower than the normal side. This can occur in patients with any condition that causes a leg-length discrepancy, such as developmental dysplasia of the hip, Legg disease, or femoral shortening

Scabies

Risk Factors

- Personal skin-to-skin contact (e.g., sexual promiscuity, crowding, nosocomial infection)

- Poor nutritional status, poverty, homelessness, and poor hygiene

- Seasonal variation: Incidence may be higher in the winter than in the summer (may be due to overcrowding).

- Immunocompromised patients including those with HIV/AIDS are at increased risk of developing severe (crusted/Norwegian) scabies.

History

- Generalized itching is often severe and worse at night.

- Determine any contact with infected individuals.

- Initial infection may be asymptomatic.

- Symptoms may develop after 3–6 weeks.

Physical Exam

- Lesions (inflammatory, erythematous, pruritic papules) most commonly located in the finger webs, flexor surfaces of the wrists, elbows, axillae, buttocks, genitalia, feet, and ankles

- Burrows (thin, curvy, elevated lines in the upper epidermis that measure 1–10 mm) may be seen in involved areas; these are considered a pathognomic sign of scabies.

- Secondary erosions or excoriations

- Pustules (if secondarily infected)

- Nodules in covered areas (buttocks, groin, axillae)

- Crusted scabies (Norwegian scabies) is a psoriasiform dermatosis occurring with hyperinfestation with thousands of mites (more common in immunosuppressed patients).

Geriatric Considerations

- The elderly often itch more severely despite fewer cutaneous lesions and are at risk for extensive infestations, perhaps related to a decline in cell-mediated immunity. There may be back involvement in those who are bedridden.

Pediatric Considerations

- Infants and very young children often present with vesicles, papules, and pustules and have more widespread involvement, including the hands, palms, feet, soles, body folds, and head (rare for adults).

Diagnostic Tests & Interpretation

- Definitive diagnosis requires microscopic identification of mite, eggs, or feces.

- Failure to find mite does not rule out scabies

Initial lab tests

- Complete blood count (CBC) is rarely needed but may show eosinophilia.

Diagnostic Procedures/Surgery

- Examination of skin with magnifying lens:

- Look for typical burrows in finger webs and on flexor aspects of the wrists and penis.

- Look for a dark point at the end of the burrow (the mite).

- Presumptive diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, skin lesions, and identification of burrow

- The mite can be extracted with a 25-gauge needle and examined microscopically.

- Mineral oil mounts

- Place a drop of mineral oil over a suspected lesion. Nonexcoriated papules or vesicles also may be sampled.

- Scrape the lesion with a no. 15 surgical blade.

- Examine under a microscope for mites, eggs, egg casings, or feces.

- Scraping from under fingernails often may be positive.

- Potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mount not recommended because it can dissolve mite pellets (1

- Burrow ink test

- If burrows are not obvious, apply blue–black ink to an area of rash. Wash off the ink with alcohol. A burrow should remain stained and become more evident.

- Then apply mineral oil, scrape, and observe microscopically, as noted previously.

- Epiluminescence microscopy and high-resolution video dermatoscopy are expensive and have not been proven to be more sensitive than skin scraping (2,3)[C].

Treatment

- Medication

First Line

- Permethrin is the most effective topical agent for scabies (5)[A]. 5% cream (Elimite, Acticin):

- After bathing or showering, apply cream from the neck to the soles of the feet; then wash off after 8–14 h. A 2nd application 1 week later is recommended if new lesions develop.

- 30 g is usually adequate for an adult.

- Side effects include itching and stinging (minimal absorption).

Pediatric Considerations

- Permethrin may be used on infants. In children <5 years of age, the cream should be applied to the head and neck as well as to the entire body.

P.1175

Second Line

- Crotamiton (Eurax) 10% cream:

- Apply from the neck down for 24 h, rinse off, then reapply for an additional 24 h, and then thoroughly wash off.

- Nodular scabies: Apply to nodules for 24 h, rinse off, then reapply for an additional 24 h, and then thoroughly wash off.

- Ivermectin (Stromectol):

- Not Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for scabies; 200–250 µg/kg as single dose; repeated in 1 week

- May need higher doses or many need to use in combination with topical scabicide for HIV-positive patients

- Precipitated sulfur 5–10% in petrolatum: Apply to the entire body from the neck down for 24 h, rinse by bathing, then repeat for 2 more days (3 days total). It is malodorous and messy but is thought to be safer than lindane, especially in infants <6 months of age, and safer than permethrin in infants <2 months of age.

- Lindane (Kwell) 1% lotion:

- Apply to all skin surfaces from the neck down and wash off 6–8 h later.

- 2 applications 1 week apart are recommended but may increase the risk of toxicity.

- 2 oz is usually adequate for an adult.

- Side effects: Neurotoxicity (seizures, muscle spasms), aplastic anemia

- Contraindications: Uncontrolled seizure disorder, premature infants

- Precautions: Use on excoriated skin, immunocompromised patients, conditions that may increase risk of seizures, or medications that decrease seizure threshold

- Possible interactions: Concomitant use with medications that lower the seizure threshold

Alert

Lindane: FDA black box warning of severe neurologic toxicity; use only when 1st-line agents have failed.

Pediatric Considerations

The FDA recommends caution when using lindane in patients who weigh <50 kg. It is not recommended for infants and is contraindicated in premature infants.

Pregnancy Considerations

- Permethrin is category B and lindane and crotamiton are category C drugs.

- Permethrin is considered compatible with lactation, but if permethrin is used while breast-feeding, the infant should be bottle fed until the cream has been thoroughly washed off.

Additional Treatment

General Measures

- Treat all intimate contacts and close household and family members.

- Wash all clothing, bed linens, and towels in hot (60°C) water or dry clean.

- Personal items that cannot be washed or dry cleaned should be sealed in a plastic bag for 3–5 days.

- Some itching and dermatitis commonly persists for 10–14 days and can be treated with antihistamines and/or topical or oral corticosteroids.

- Patient Education

- Patients should be instructed on proper application and cautioned not to overuse the medication when applying it to the skin.

- Patient fact sheet is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): http://www.cdc.gov.

Prognosis

- Lesions begin to regress in 1–2 days, along with the worst itching, but eczema and itching may persist for up to 1 month after treatment.

- Nodular lesions may persist for several weeks, perhaps necessitating intralesional or systemic steroids.

- Some instances of lindane-resistant scabies have now been reported. These do respond to permethrin.

Complications

- Poor sleep owing to pruritus

- Social stigma

- Secondary bacterial infection

- Sepsis

- Glomerulonephritis

- Eczema

- Pyoderma

- Postscabetic pruritus

- Nodules (nodular scabies) may persist for weeks to months after treatment.

References

1. Chosidow O. Scabies. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1718–27.

2. Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Scabies. Lancet. 2006;367:1767–74.

3. Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: An update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 3):S153–59.

4. Hengge UR, Currie BJ, Jäger G et al. Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:769–79.

5. Stong M, Johnstone PW. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2007:3.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Drugs for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

The goals of drug therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are to reduce symptoms such as dyspnea, improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, and decrease complications of the disease such as acute exacerbations. Other guidelines for treatment of this condition have been published or updated in recent years.1,2

SMOKING CESSATION — The primary strategy for preventing and minimizing the risk of COPD is to help patients stop smoking. Cigarette smoking causes 85% of all COPD cases. Smoking cessation offers health benefits at all stages of the disease and can slow the decline of lung function. Counseling and pharmacotherapy can help patients stop smoking. Effective medications include varenicline (Chantix), nicotine replacement therapies and bupropion (Zyban, and others).3 Varenicline offers a unique mechanism of action as a partial nicotinic receptor agonist, but the current labeling includes precautions regarding possible neuropsychiatric side effects.4 Combinations of smoking cessation therapies may offer additional benefit.5

INHALATION DEVICES — Guidelines are available for choosing among aerosol delivery devices.6 Inhaled drugs are available in the US mainly in pressurized metered-dose inhalers (MDIs), which require a propellant, and dry powder inhalers (DPIs), which do not. Spacers used with MDIs may improve drug delivery, decrease mouth deposition, and require less hand-breath coordination. Nebulizers may be easier to use for some patients, such as the elderly, but more time is required to administer the drug with a nebulizer, and the device, which is usually not portable, requires greater care in cleaning.7

SHORT-ACTING BRONCHODILATORS — For patients with intermittent symptoms, therapy with an inhaled short-acting bronchodilator is recommended for acute relief. Typically, these patients have mild airflow obstruction and symptoms are usually associated with exertion. Short-acting agents, which include inhaled beta2-agonists such as albuterol and the anticholinergic ipratropium, can relieve symptoms and improve exercise tolerance. Short-acting beta2-agonists have a more rapid onset (<5 minutes) than ipratropium (15 minutes). With chronic use, short-acting beta2-agonists have a duration of action of less than 4 hours, while ipratropium may continue to act for 6 hours (MDI) or as long as 8 hours (nebulized). There is no convincing evidence that any one of the inhaled short-acting beta2-agonists is more effective than any other.

Combination Therapy – Combining a beta2-agonist with ipratropium has an additive effect. The combination of ipratropium/albuterol has been more effective than either drug alone and is available in a single inhaler.

Adverse Effects – Beta2-agonists can cause tachycardia, skeletal muscle tremors and cramping, headache, palpitations, prolongation of the QT interval, insomnia, hypokalemia and increases in serum glucose. They require caution in patients with cardiovascular disease; unstable angina and myocardial infarction have been reported. Tolerance to these effects occurs with chronic therapy.

Ipratropium is a quaternary ammonium anticholinergic agent with limited systemic absorption. The most common adverse effect is dry mouth. Pharyngeal irritation, urinary retention and increases in intraocular pressure may occur. Anticholinergics should be used with caution in patients with glaucoma and in those with symptomatic prostatic hypertrophy or bladder neck obstruction.

LONG-ACTING BRONCHODILATORS — For patients with evidence of significant airflow obstruction and chronic symptoms, regular treatment with a long-acting bronchodilator is recommended. Choices include an inhaled long-acting beta2-agonist or an anticholinergic agent.

Long-acting beta2-agonists are intended to provide sustained bronchodilation for at least 12 hours. They have been shown to improve lung function and quality of life and to lower exacerbation rates in patients with COPD.7

All long-acting beta2-agonist products in the US include a boxed warning about an increased risk of asthma-related deaths; there is no evidence to date that patients with COPD are at risk. The adverse effects of long-acting beta2-agonists are similar to those of the short-acting agents. Tolerance to the therapeutic effects of long-acting beta2-agonists can occur with continued use.

Tiotropium is the only long-acting anticholinergic agent available in the US. Its long duration of action allows once-daily dosing, and there is no evidence of tolerance to its therapeutic benefits. The UPLIFT trial enrolled 5993 patients with COPD and randomized them to either tiotropium or placebo, in addition to their usual medications, for 4 years. Spirometry, quality-of-life scores, and exacerbation and hospitalization rates all improved compared to placebo in tiotropium-treated patients, but treatment did not reduce the rate of decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) during the study period.8,9 Tiotropium is generally well tolerated and appears to be safe.10 Adverse effects are similar to those of ipratropium.11

Combination Therapy – When patients are not adequately controlled with a single long-acting bronchodilator, combining tiotropium with a long-acting beta2-agonist may be helpful.12

THEOPHYLLINE — Slow-release theophylline can be used as an oral alternative or in addition to inhaled bronchodilators (see Table 4). Its primary mechanism of action is bronchodilation. Because of significant inter- and intra-patient variability in theophylline clearance, dosing requirements vary. The drug has a narrow therapeutic index; monitoring is warranted periodically to maintain serum concentrations between 5 and 12 mcg/mL for treatment of COPD.

Adverse Effects – At theophylline serum concentrations higher than 12-15 mcg/mL, nausea, nervousness, headache and insomnia occur with increasing frequency in patients with COPD. Vomiting, hypokalemia, hyperglycemia, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmias, tremors, neuromuscular irritability and seizures can also occur at higher serum concentrations. Theophylline is metabolized in the liver, primarily by CYP1A2 and CYP3A4. Any drug that is an inhibitor or inducer of these enzymes can affect theophylline metabolism.13 Clearance of theophylline is reduced in the elderly and in patients with liver disease or heart failure.

CORTICOSTEROIDS — In patients with severe COPD (FEV1 <50%) who experience frequent exacerbations while receiving one or more long-acting bronchodilators, addition of an inhaled corticosteroid is recommended to reduce the number of exacerbations. In the 3-year, double-blind TORCH study of more than 6000 patients with COPD, the combination of salmeterol/ fluticasone reduced exacerbation frequency by 25% compared to placebo, and by 12% compared to salmeterol alone.14 The results of several large, international studies indicate that inhaled corticosteroids do not slow the progression of COPD.15

Adverse Effects – Risks of inhaled corticosteroid therapy are dose-related. Local effects on the mouth and pharynx include candidiasis and dysphonia. Systemic absorption of inhaled corticosteroids has been associated with skin bruising, cataracts, reduced bone mineral density and an increased risk of fractures. Several large studies have found an increased risk of pneumonia associated with high doses (1000 mcg/day) of fluticasone.16

Long-term treatment with oral corticosteroids is not recommended in COPD. The risks of such treatment include myopathy, glucose intolerance, weight gain and immunosuppression.

TRIPLE-THERAPY REGIMENS — Two short-term studies (2-12 weeks) have demonstrated a benefit with triple therapy (tiotropium, formoterol or salmeterol, and fluticasone or budesonide) compared to 1 or 2 agents in relieving symptoms such as dyspnea and in improving lung function.17,18 In one of these studies, the number of severe exacerbations decreased by 62% with triple therapy. In a retrospective cohort study, the triple-combination regimen reduced overall mortality by 40%.19

OXYGEN THERAPY — For patients with severe hypoxemia, use of long-term supplemental oxygen therapy has been shown to increase survival and quality of life.20 Oxygen therapy may also increase exercise capacity in patients with mild or moderate hypoxemia, but its long-term benefits in such patients are unclear.21

IMMUNIZATIONS — Patients with COPD should receive influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine to reduce their risk of infection and complications from these pathogens.22

PULMONARY REHABILITATION — The benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation programs are well established for patients with COPD. Pulmonary rehabilitation can reduce dyspnea and improve functional capacity and quality of life, as well as reduce the number of hospitalizations.23

ACUTE EXACERBATIONS — A major focus of the chronic treatment of COPD is to reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, which have a significant effect on the course of the disease. When exacerbations occur, treatment includes intensification of short-acting bronchodilators, short-term therapy with systemic corticosteroids, and usually a course of antimicrobial therapy. Short-acting beta2-agonists are generally used first. Among patients requiring hospitalization, oral prednisone doses of 40-60 mg daily for up to two weeks appeared to be as effective as more aggressive corticosteroid dosing.24 The use of ventilatory support and supplemental oxygen therapy has been shown to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with acute exacerbations.20

SUMMARY — Patients with COPD should stop smoking; pharmacotherapy may be helpful, especially with varenicline (Chantix). Patients with mild, intermittent symptoms can be treated with inhaled short-acting bronchodilators for symptom relief. When symptoms become more severe or persistent, inhaled long-acting bronchodilators may be used. Regular use of long-acting bronchodilators can decrease the number of acute exacerbations. Combinations of a beta2-agonist with an anticholinergic can be used for patients inadequately controlled with a single agent. For patients with severe COPD who experience frequent exacerbations, addition of an inhaled corticosteroid (triple therapy) is recommended. For patients with severe hypoxemia, oxygen therapy can improve survival.

SMOKING CESSATION — The primary strategy for preventing and minimizing the risk of COPD is to help patients stop smoking. Cigarette smoking causes 85% of all COPD cases. Smoking cessation offers health benefits at all stages of the disease and can slow the decline of lung function. Counseling and pharmacotherapy can help patients stop smoking. Effective medications include varenicline (Chantix), nicotine replacement therapies and bupropion (Zyban, and others).3 Varenicline offers a unique mechanism of action as a partial nicotinic receptor agonist, but the current labeling includes precautions regarding possible neuropsychiatric side effects.4 Combinations of smoking cessation therapies may offer additional benefit.5

INHALATION DEVICES — Guidelines are available for choosing among aerosol delivery devices.6 Inhaled drugs are available in the US mainly in pressurized metered-dose inhalers (MDIs), which require a propellant, and dry powder inhalers (DPIs), which do not. Spacers used with MDIs may improve drug delivery, decrease mouth deposition, and require less hand-breath coordination. Nebulizers may be easier to use for some patients, such as the elderly, but more time is required to administer the drug with a nebulizer, and the device, which is usually not portable, requires greater care in cleaning.7

SHORT-ACTING BRONCHODILATORS — For patients with intermittent symptoms, therapy with an inhaled short-acting bronchodilator is recommended for acute relief. Typically, these patients have mild airflow obstruction and symptoms are usually associated with exertion. Short-acting agents, which include inhaled beta2-agonists such as albuterol and the anticholinergic ipratropium, can relieve symptoms and improve exercise tolerance. Short-acting beta2-agonists have a more rapid onset (<5 minutes) than ipratropium (15 minutes). With chronic use, short-acting beta2-agonists have a duration of action of less than 4 hours, while ipratropium may continue to act for 6 hours (MDI) or as long as 8 hours (nebulized). There is no convincing evidence that any one of the inhaled short-acting beta2-agonists is more effective than any other.

Combination Therapy – Combining a beta2-agonist with ipratropium has an additive effect. The combination of ipratropium/albuterol has been more effective than either drug alone and is available in a single inhaler.

Adverse Effects – Beta2-agonists can cause tachycardia, skeletal muscle tremors and cramping, headache, palpitations, prolongation of the QT interval, insomnia, hypokalemia and increases in serum glucose. They require caution in patients with cardiovascular disease; unstable angina and myocardial infarction have been reported. Tolerance to these effects occurs with chronic therapy.

Ipratropium is a quaternary ammonium anticholinergic agent with limited systemic absorption. The most common adverse effect is dry mouth. Pharyngeal irritation, urinary retention and increases in intraocular pressure may occur. Anticholinergics should be used with caution in patients with glaucoma and in those with symptomatic prostatic hypertrophy or bladder neck obstruction.

LONG-ACTING BRONCHODILATORS — For patients with evidence of significant airflow obstruction and chronic symptoms, regular treatment with a long-acting bronchodilator is recommended. Choices include an inhaled long-acting beta2-agonist or an anticholinergic agent.

Long-acting beta2-agonists are intended to provide sustained bronchodilation for at least 12 hours. They have been shown to improve lung function and quality of life and to lower exacerbation rates in patients with COPD.7

All long-acting beta2-agonist products in the US include a boxed warning about an increased risk of asthma-related deaths; there is no evidence to date that patients with COPD are at risk. The adverse effects of long-acting beta2-agonists are similar to those of the short-acting agents. Tolerance to the therapeutic effects of long-acting beta2-agonists can occur with continued use.

Tiotropium is the only long-acting anticholinergic agent available in the US. Its long duration of action allows once-daily dosing, and there is no evidence of tolerance to its therapeutic benefits. The UPLIFT trial enrolled 5993 patients with COPD and randomized them to either tiotropium or placebo, in addition to their usual medications, for 4 years. Spirometry, quality-of-life scores, and exacerbation and hospitalization rates all improved compared to placebo in tiotropium-treated patients, but treatment did not reduce the rate of decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) during the study period.8,9 Tiotropium is generally well tolerated and appears to be safe.10 Adverse effects are similar to those of ipratropium.11

Combination Therapy – When patients are not adequately controlled with a single long-acting bronchodilator, combining tiotropium with a long-acting beta2-agonist may be helpful.12

THEOPHYLLINE — Slow-release theophylline can be used as an oral alternative or in addition to inhaled bronchodilators (see Table 4). Its primary mechanism of action is bronchodilation. Because of significant inter- and intra-patient variability in theophylline clearance, dosing requirements vary. The drug has a narrow therapeutic index; monitoring is warranted periodically to maintain serum concentrations between 5 and 12 mcg/mL for treatment of COPD.

Adverse Effects – At theophylline serum concentrations higher than 12-15 mcg/mL, nausea, nervousness, headache and insomnia occur with increasing frequency in patients with COPD. Vomiting, hypokalemia, hyperglycemia, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmias, tremors, neuromuscular irritability and seizures can also occur at higher serum concentrations. Theophylline is metabolized in the liver, primarily by CYP1A2 and CYP3A4. Any drug that is an inhibitor or inducer of these enzymes can affect theophylline metabolism.13 Clearance of theophylline is reduced in the elderly and in patients with liver disease or heart failure.

CORTICOSTEROIDS — In patients with severe COPD (FEV1 <50%) who experience frequent exacerbations while receiving one or more long-acting bronchodilators, addition of an inhaled corticosteroid is recommended to reduce the number of exacerbations. In the 3-year, double-blind TORCH study of more than 6000 patients with COPD, the combination of salmeterol/ fluticasone reduced exacerbation frequency by 25% compared to placebo, and by 12% compared to salmeterol alone.14 The results of several large, international studies indicate that inhaled corticosteroids do not slow the progression of COPD.15

Adverse Effects – Risks of inhaled corticosteroid therapy are dose-related. Local effects on the mouth and pharynx include candidiasis and dysphonia. Systemic absorption of inhaled corticosteroids has been associated with skin bruising, cataracts, reduced bone mineral density and an increased risk of fractures. Several large studies have found an increased risk of pneumonia associated with high doses (1000 mcg/day) of fluticasone.16

Long-term treatment with oral corticosteroids is not recommended in COPD. The risks of such treatment include myopathy, glucose intolerance, weight gain and immunosuppression.

TRIPLE-THERAPY REGIMENS — Two short-term studies (2-12 weeks) have demonstrated a benefit with triple therapy (tiotropium, formoterol or salmeterol, and fluticasone or budesonide) compared to 1 or 2 agents in relieving symptoms such as dyspnea and in improving lung function.17,18 In one of these studies, the number of severe exacerbations decreased by 62% with triple therapy. In a retrospective cohort study, the triple-combination regimen reduced overall mortality by 40%.19

OXYGEN THERAPY — For patients with severe hypoxemia, use of long-term supplemental oxygen therapy has been shown to increase survival and quality of life.20 Oxygen therapy may also increase exercise capacity in patients with mild or moderate hypoxemia, but its long-term benefits in such patients are unclear.21

IMMUNIZATIONS — Patients with COPD should receive influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine to reduce their risk of infection and complications from these pathogens.22

PULMONARY REHABILITATION — The benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation programs are well established for patients with COPD. Pulmonary rehabilitation can reduce dyspnea and improve functional capacity and quality of life, as well as reduce the number of hospitalizations.23

ACUTE EXACERBATIONS — A major focus of the chronic treatment of COPD is to reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, which have a significant effect on the course of the disease. When exacerbations occur, treatment includes intensification of short-acting bronchodilators, short-term therapy with systemic corticosteroids, and usually a course of antimicrobial therapy. Short-acting beta2-agonists are generally used first. Among patients requiring hospitalization, oral prednisone doses of 40-60 mg daily for up to two weeks appeared to be as effective as more aggressive corticosteroid dosing.24 The use of ventilatory support and supplemental oxygen therapy has been shown to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with acute exacerbations.20

SUMMARY — Patients with COPD should stop smoking; pharmacotherapy may be helpful, especially with varenicline (Chantix). Patients with mild, intermittent symptoms can be treated with inhaled short-acting bronchodilators for symptom relief. When symptoms become more severe or persistent, inhaled long-acting bronchodilators may be used. Regular use of long-acting bronchodilators can decrease the number of acute exacerbations. Combinations of a beta2-agonist with an anticholinergic can be used for patients inadequately controlled with a single agent. For patients with severe COPD who experience frequent exacerbations, addition of an inhaled corticosteroid (triple therapy) is recommended. For patients with severe hypoxemia, oxygen therapy can improve survival.

Drugs for Asthma

No truly new drugs have been approved for treatment of asthma since omalizumab (Xolair) in 2003, but some randomized controlled trials of older drugs have been published, and new guidelines have become available.1

INHALATION DEVICES

Inhalation is the preferred route of delivery for most asthma drugs. Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which have ozone-depleting properties, are being phased out as propellants in metered-dose inhalers; albuterol inhalers with CFCs will not be available in the US after December 31, 2008. Non-chlorinated hydrofluoroalkane (HFA) propellants, which do not deplete the ozone layer, will replace them.2

Metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) require coordination of inhalation with hand-actuation of the device. Valved holding chambers (VHCs) or spacers can help young children or elderly patients use MDIs effectively. VHCs have one-way valves that prevent the patient from exhaling into the device, eliminating the need for coordinated actuation and inhalation. Spacers are open tubes placed on the mouthpiece of an MDI. Both VHCs and spacers retain the large particles emitted from the MDI, preventing their deposition in the oropharynx and leading to a higher proportion of small respirable particles being inhaled.

Dry powder inhalers (DPIs), which are breath-actuated, can be used in patients who are capable of performing a rapid deep inhalation.

Delivery of inhaled asthma medications through a nebulizer with a face mask or mouthpiece is less dependent on the patient’s coordination and cooperation, but more time-consuming than delivery through an MDI or DPI.3

INHALED CORTICOSTEROIDS

For mild, moderate or severe persistent asthma, inhaled corticosteroids are the most effective long-term treatment for control of symptoms in all age groups. In randomized, controlled trials, they have been significantly more effective than leukotriene modifiers, long-acting beta-2 agonists, cromolyn or theophylline in improving pulmonary function, preventing symptoms and exacerbations, reducing the need for emergency department treatment, and decreasing deaths due to asthma. The majority of the benefit is achieved at relatively low doses. The optimal dose for a given patient may increase or decrease over time, but should always be the lowest that maintains asthma control. Doses vary depending on the inhaled corticosteroid and the delivery device; these medications are not precisely interchangeable on a per mcg or per puff basis.

Adverse Effects – Local adverse effects of inhaled corticosteroids may include oral candidiasis (thrush), dysphonia (hoarseness), and reflex cough and bronchospasm. Use of a VHC or a spacer and rinsing the mouth after use may reduce the incidence of these effects. No clinically relevant changes occur in hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal axis function with low- or medium-dose inhaled corticosteroids, but children’s growth should be monitored. Patients who require high-dose inhaled corticosteroid treatment should be monitored for osteoporosis and development of cataracts.

SHORT-ACTING BETA-2 AGONISTS

Inhaled short-acting selective beta-2 agonists (albuterol, levalbuterol, pirbuterol) increase airflow within 3-5 minutes; they are the medications of first choice for treating acute wheeze, chest tightness, cough and shortness of breath as needed, and for preventing exercise-induced bronchospasm. Regularly scheduled daily use is not recommended. Use of these agents for symptom relief on more than 2 days per week suggests inadequate control of asthma, and the need for starting or possibly increasing the dose of an inhaled corticosteroid. Over-reliance of asthma patients on a short-acting beta-2 agonist has been associated with an increased risk of death.4 Levalbuterol and racemic albuterol (which is 50% levalbuterol, the pharmacologically active isomer of the racemate) in recommended doses produce comparable bronchodilation and have comparable adverse effects.5,6

Adverse Effects – Systemic toxicity from short-acting beta-2 agonists is uncommon, but may occur with high doses or use in elderly patients. Adverse effects can include paradoxical bronchospasm, tachycardia and other cardiovascular symptoms, skeletal muscle tremor, headache, hypokalemia and hyperglycemia.

LONG-ACTING BETA-2 AGONISTS

Long-acting beta-2 agonists should be used in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid; they should not be used to relieve acute asthma symptoms and are not recommended for use as monotherapy in the treatment of asthma. Addition of salmeterol (Serevent) or formoterol (Foradil) to the treatment of patients with persistent asthma not well controlled on low-dose inhaled corticosteroids improves lung function, decreases symptoms, and reduces exacerbations and rescue use of short-acting beta-2 agonists.7,8,9 Long-acting beta-2 agonists are best administered in a fixeddose combination in the same inhaler with an inhaled corticosteroid. How the fixed-dose combinations of fluticasone/salmeterol and budesonide/formoterol compare with each other remains to be determined.10

Adverse Effects – Addition of a long-acting beta-2 agonist to inhaled corticosteroid therapy has been reported in a few patients to cause down-regulation of the beta-2 receptor with loss of the bronchoprotective effect from rescue therapy with a short-acting beta-2 agonist.11 In one large trial in patients with asthma in which salmeterol or placebo was added to usual asthma treatment, 13 of 13,176 salmeterol-treated patients died of asthma, compared to only 3 of 13,179 placebo-treated patients12; therefore, a black box warning about a higher risk of asthmarelated death was added to the package inserts of all preparations containing a long-acting beta-2 agonist. However, a matched case-control study found that long-acting beta-2 agonist use during the prior 3 months was not associated with increased risk of death from asthma.13 In doses higher than recommended, long-acting beta-2 agonists can produce clinically relevant tremor, cardiovascular effects including tachycardia and QTc interval prolongation, hypokalemia and hyperglycemia.

LEUKOTRIENE MODIFIERS

Leukotriene modifiers are used as an alternative to inhaled corticosteroids for persistent asthma, but they are less effective. They can be used as an additional treatment for patients with mild or moderate persistent asthma not well controlled on inhaled corticosteroids, but addition of a long-acting beta-2 agonist (in the same inhaler) is preferred. Leukotriene modifiers are not recommended for treatment of acute asthma symptoms, and their dose-response curve is flat. Most published efficacy data relate to montelukast, and it is the only one of these drugs approved by the FDA for use in preventing exercise-induced asthma.

Adverse Effects – Churg-Strauss vasculitis has been reported with montelukast and zafirlukast, but in most cases it could have been a consequence of corticosteroid withdrawal rather than a direct effect of the leukotriene modifier. Montelukast is less likely than zafirlukast or zileuton to cause drug-drug interactions or hepatitis, and is generally considered safe for long-term use, but the FDA has received post-marketing reports of psychiatric symptoms including suicidality. Zafirlukast is a moderate inhibitor of CYP2C9 that increases the serum concentrations of concomitantly administered medications such as warfarin (Coumadin, and others). Zileuton is a moderate inhibitor of CYP1A2 that inhibits the metabolism of theophylline and many other drugs.14 Both zafirlukast and zileuton have been reported to cause life-threatening hepatic injury; alanine aminotransferase should be monitored, and patients should be warned to discontinue the medication immediately if abdominal pain, nausea, jaundice, itching or lethargy occur.

CROMOLYN SODIUM

Cromolyn is now infrequently used for treatment of mild persistent asthma. Although relatively ineffective compared to inhaled corticosteroids (it may take weeks to detect any benefit), it has an excellent safety profile, except for occasional complaints of cough and irritation. Nedocromil, which was similar to cromolyn, is no longer available.

THEOPHYLLINE

Sustained-release theophylline is now infrequently used for persistent asthma, taken either alone or concurrently with an inhaled corticosteroid. Monitoring of serum theophylline concentrations and keeping them between 5 and 15 mcg/mL is recommended. Many other drugs used concomitantly can interact with theophylline, either by increasing its metabolism and decreasing its serum concentrations and efficacy, or by decreasing its metabolism, leading to higher concentrations and toxicity.14

Adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, nervousness, headache and insomnia. At high serum concentrations, hypokalemia, hyperglycemia, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmias, tremor, neuromuscular irritability, seizures and death can occur.

ANTICHOLINERGICS

Ipratropium bromide (Atrovent, and others), an inhaled short-acting anticholinergic bronchodilator used to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), has also been used as an alternative to short-acting beta-2 agonists in patients with asthma who cannot tolerate them; it should not be used in the treatment of persistent asthma and has not been approved for any use in asthma by the FDA. Tiotropium bromide (Spiriva), an inhaled long-acting anticholinergic agent, is also used to treat COPD, but it has not been studied in persistent asthma, and is not FDA-approved for use in asthma.

Adverse effects from these agents include dry mouth, pharyngeal irritation, urinary retention, and increased intraocular pressure; they should be used with caution in patients with glaucoma, prostatic hypertrophy or bladder neck obstruction.

ANTI-IgE ANTIBODY

Omalizumab (Xolair) is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that prevents IgE from binding to mast cells and basophils, thereby preventing release of inflammatory mediators after allergen exposure. It is approved by the FDA for adjunctive use in patients at least 12 years old with well-documented specific allergies and moderate to severe persistent asthma that is not well controlled on an inhaled corticosteroid with or without a long-acting beta-2 agonist. Subcutaneous injection of omalizumab every 2-4 weeks has been reported to lead to fewer asthma exacerbations, with a modest (inhaled) corticosteroid-sparing effect.15,16 It is expensive.17

Adverse Effects – Adverse effects of omalizumab include injection site pain and bruising in up to 20% of patients. Anaphylaxis, usually occurring within 2 hours after injection but sometimes up to 4 days later, has been reported in 0.2% of patients, resulting in an FDA black box warning.18 An asthma task force has advised keeping patients under observation for 2 hours after the first three omalizumab injections, and for 30 minutes after subsequent injections, and educating patients about recognition of anaphylaxis and the need for prompt treatment with self-injected epinephrine.19 Serum sickness and Churg-Strauss vasculitis have occurred rarely after omalizumab injection. Malignant neoplasms have been reported in 0.5% of patients receiving omalizumab, compared to 0.2% of those receiving placebo; cause and effect have not been established.

EXERCISE-INDUCED BRONCHOSPASM

Exercise-induced bronchospasm may be the only manifestation of asthma in patients with mild disease. Short-acting inhaled beta-2 agonists used just before exercise will prevent it in more than 80% of patients; they have a duration of action of 2-3 hours. Long-acting beta-2 agonists can prevent exercise-induced bronchospasm for up to 12 hours, but if they are administered on a regular basis, the protection may wane and not last throughout the day. Montelukast decreases exercise-induced bronchospasm in up to 50% of patients; its onset of action has been reported to begin as soon as 2 hours after administration and persist for up to 24 hours,20 with no loss of protection over time. In patients whose exercise-induced bronchospasm occurs because of poorly controlled persistent asthma, daily long-term anti-inflammatory medication should be started or its dosage increased.21

ASTHMA DURING PREGNANCY

Maternal asthma increases the risk of pre-eclampsia, perinatal mortality, pre-term birth and low birth weight. It is safer for pregnant women who have asthma to be treated with asthma medications than to have poorly controlled asthma symptoms. Albuterol is the preferred short-acting beta-2 agonist for use in pregnancy because of its excellent safety profile. Inhaled corticosteroids are the preferred long-term controller medication. More data are available on the safety of budesonide during pregnancy than on that of other inhaled corticosteroids. Long-acting beta-2 agonists, used in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid, also appear to be safe in pregnancy. Limited data suggest that montelukast appears to be safe.22 Animal studies have found teratogenicity with zileuton.23

Table 1 - Revised 11/13/08: The last sentence of footnote 7 was incomplete; "within one hour after morning and evening meals" was added.

ASTHMA IN INFANTS AND CHILDREN

For infants and children with mild intermittent asthma, a short-acting beta-2 agonist should be used as needed. One report suggested that a short course of montelukast started at the first sign of an asthma episode may be beneficial.24 For mild, moderate or severe persistent asthma, inhaled corticosteroids are the preferred long-term treatment for control of symptoms25,26; however, they do not affect the underlying severity or progression of the disease.27,28

Inhaled corticosteroids can be delivered through a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) with a valved holding chamber (VHC) and face mask or mouthpiece, or through a nebulizer or dry powder inhaler (DPI). Inhaled corticosteroids given in low doses even for extended periods of time are generally safe for use in infants and children, but linear growth should be monitored. Low- to medium-dose inhaled corticosteroids may reduce growth velocity slightly during the first year of treatment, but usually not after that, and final height appears not to be affected.29

Dry powder inhalers (DPIs) are not suitable for use in infants or young children. Fluticasone and mometasone dry powder inhalers are approved for children as young as four years of age, but children that young may have difficulty inhaling rapidly or deeply enough to use the device effectively. Budesonide nebulizer suspension is approved for children as young as one year of age. Montelukast is also approved for use in children as young as one year.

IMMUNOTHERAPY

In selected patients with allergic asthma, specific immunotherapy (“allergy shots”) may provide long-lasting benefits in reducing asthma symptoms and the need for medications.30

FAILURE OF PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Lack of adherence to the prescribed medication regimen is the most common cause of pharmacologic failure in asthma. Co-morbid conditions that may make asthma management more difficult include chronic rhinitis/sinusitis,31 gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD),32 obesity,33,34 and depression and psychosocial factors. Some patients with asthma may concurrently be taking aspirin or other NSAIDs that can cause asthma symptoms. Oral or topical nonselective betaadrenergic blockers such as propranolol (Inderal, and others) or timolol (Blocadren, and others) can precipitate bronchospasm in patients with asthma and decrease the bronchodilating effect of beta-2 agonists.

Patients with asthma who continue to smoke do not respond optimally to inhaled corticosteroids8; they may respond better to montelukast.35 Asthmatics should also avoid exposure to second-hand smoke, airborne pollutants, and allergens.36 Patients with asthma may also benefit from meeting with trained asthma educators.37

MANAGING EXACERBATIONS OF ASTHMA

Patient education, including a written Asthma Action Plan, should guide the initial self-management of exacerbations at home.37 Such a plan involves recognition of early signs of worsening asthma, appropriate intensification of treatment by increasing the dose of inhaled short-acting beta-2 agonists, and in some patients, initiating a short course of an oral corticosteroid; patients should also communicate with their clinician about symptoms and responsiveness to intervention. Doubling the dose of inhaled corticosteroids is not effective.38

Oral Corticosteroids – Oral systemic corticosteroids are the most effective drugs available for exacerbations of asthma incompletely responsive to bronchodilators. Even when an acute exacerbation responds to bronchodilators, addition of a short course of an oral corticosteroid can decrease symptoms and may prevent a relapse. For asthma exacerbations, daily systemic corticosteroids are generally required for only 3-10 days, after which no tapering is needed.39

Oral corticosteroids should only rarely be used as long-term control medications and then only in that small minority of patients with uncontrolled severe persistent asthma. In this situation, an oral corticosteroid should be given at the lowest effective dose, preferably on alternate mornings, in order to produce the least toxicity.39 Steroid resistance has been recognized in some patients with asthma.40

Potential adverse effects of long-term oral corticosteroids include endocrinologic effects such as adrenal suppression, weight gain, Cushingoid stigmata and diabetes mellitus; musculoskeletal effects such as osteoporosis, aseptic necrosis and myopathy; ophthalmologic effects such as cataracts and glaucoma; dermatologic effects such as dermal thinning, striae, acne, hirsutism and delayed wound healing; psychologic effects such as mood swings, depression and psychosis; metabolic effects such as hypokalemia, hyperglyclemia, and hyperlipidemia; and cardiovascular effects such as hypertension. Immune function is potentially impaired, and re-activation of latent tuberculosis, herpes, varicella, and Strongyloides infections may occur. Short-term use of oral corticosteroids may cause increased appetite, weight gain, changes in mood and hypertension.

In the urgent care or emergency department setting, treatment of asthma exacerbations includes: oxygen to relieve hypoxemia; a short-acting beta-2 agonist, sometimes in combination with ipratropium, to relieve airflow obstruction; and a systemic corticosteroid to decrease airway inflammation. Ipratropium is a useful bronchodilator for patients with acute asthma symptoms who do not respond adequately to or cannot tolerate a short-acting beta-2 agonist, or who are taking nonselective beta-blockers. Severe asthma exacerbations unresponsive to the above treatments may respond to intravenous magnesium sulfate or inhalation of heliox, a mixture of helium and oxygen; helium decreases airway resistance.41

SUMMARY

For monotherapy of persistent asthma, inhaled corticosteroids are more effective than long-acting beta-2 agonists, leukotriene modifiers, theophylline or cromolyn. If regular use of an inhaled corticosteroid in a low dose does not prevent symptoms, the dose can be increased or regular daily treatment with an inhaled long-acting beta-2 agonist in the same inhaler can be started. In patients with allergic asthma, immunotherapy may provide long-lasting benefits. If severe persistent allergic asthma remains uncontrolled, omalizumab can be added in patients ≥12 years. Failure of pharmacologic treatment in asthma may occur due to lack of adherence to prescribed medication, co-morbid conditions, or ongoing exposure to tobacco smoke, airborne pollutants or allergens.

Saturday, November 19, 2011

diaper rash

i saw this case in my clinic

3 month old girl 2 days history of rash on buttocks area,no diarrhea

DIAPER RASH

3 month old girl 2 days history of rash on buttocks area,no diarrhea

DIAPER RASH

Risk Factors

- Infrequent diaper changes

- Waterproof diapers

- Improper laundering

- Family history of dermatitis

- Hot, humid weather

- Recent treatment with oral antibiotics

- Diarrhea

- Dye allergy

General PreventionAttention to hygiene during bouts of diarrhea

Pathophysiology- Fecal proteases and lipases are irritants.

- Fecal lipase and protease activity is increased by acceleration of GI transit; thus a higher incidence of irritant diaper dermatitis is observed in babies who have had diarrhea in the previous 48 h.

- Once the skin is compromised, secondary infection by C. albicans is common. 40–75% of diaper rashes that last >3 days are colonized with C. albicans.

- Bacteria may play a role in diaper dermatitis through reduction of fecal pH and resulting activation of enzymes.

- Allergy is exceedingly rare as a cause in infants.

Etiology- Irritation to skin from prolonged contact with urine or feces (2)

- Some have raised the possibility of contact allergy from the dye in disposable diapers (3).History

- Onset, duration, and change in the nature of the rash

- Presence of rashes outside the diaper area

- Associated scratching or crying

- Contact with infants with a similar rash

- Recent illness, diarrhea, or antibiotic use

- Fever

- Pustular drainage

- Lymphangitis

Physical Exam- Mild forms consist of shiny erythema ± scale.

- Margins are not always evident.

- Moderate cases have areas of papules, vesicles, and small superficial erosions.

- It can progress to well-demarcated ulcerated nodules that measure a centimeter or more in diameter.

- It is found on the prominent parts of the buttocks, medial thighs, mons pubis, and scrotum.

- Skin folds are spared or involved last.

- Tidemark dermatitis refers to the bandlike form of erythema of irritated diaper margins.

- Diaper dermatitis can cause an id (autoeczematous) reaction outside the diaper areaTreatmentMedicationFirst Line

- For a pure contact dermatitis, a low-potency topical steroid (hydrocortisone 0.5–1% t.i.d.) and removal of the offending agent should suffice.

- If candidiasis is suspected or diaper rash persists, use an antifungal such as miconazole nitrate 2% cream, miconazole powder, econazole (Spectazole), clotrimazole (Lotrimin), or ketoconazole (Nizoral) cream at each diaper change (2)[B].

- If inflammation is prominent, consider a very low-potency steroid cream such as hydrocortisone 0.5–1% t.i.d. along with an antifungal cream ± a combination product such as clioquinol-hydrocor-tisone (Vioform–hydrocortisone) cream (2)[B].

- If a secondary bacterial infection is suspected, use an antistaphylococcal oral antibiotic or mupirocin (Bactroban) ointment topically.

- Precautions: Avoid high- or moderate-potency steroids often found in combination steroid antifungal mixtures (2)[B].

Second LineSucralfate paste for resistant casesAdditional TreatmentGeneral Measures- Expose the buttocks to air as much as possible (2).

- Avoid waterproof pants during treatment (day or night); they keep the skin wet and subject to rash or infection.

- Change diapers frequently, even at night, if the rash is extensive (4).

- Superabsorbable diapers are beneficial (2,4)[B].

- Discontinue using baby lotion, powder, ointment, or baby oil (except zinc oxide).

- Disposable baby wipes contain substances that induce contact or irritant dermatitis, such as fragrance, benzalkonium chloride, and isothiazolinone or alcohol.

- Apply zinc oxide ointment or other barrier cream to the rash at the earliest sign and b.i.d. or t.i.d. (e.g., Desitin or Balmex). Thereafter, apply to clean, thoroughly dry skin (2).

- Use mild soap, and pat dry.

- Cornstarch can reduce friction. Talc powders that do not enhance the growth of yeast can provide protection against frictional injury in diaper dermatitis but do not form a continuous lipid barrier layer over the skin and obstruct the skin pores. These treatments are not recommended.

-

-

-

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)